People were endangered by the reckless speed with which I shot across the planet to answer this question. Sonic booms disordered friendly airspace; trails of flying debris ended up haphazardly beside roads; John and the cats are in hiding. I'm a mythology enthusiast and a librarian and a Mexican-flag-wavin' fan of the Aztecs in Scion, and you have basically just asked me a jackpot question.

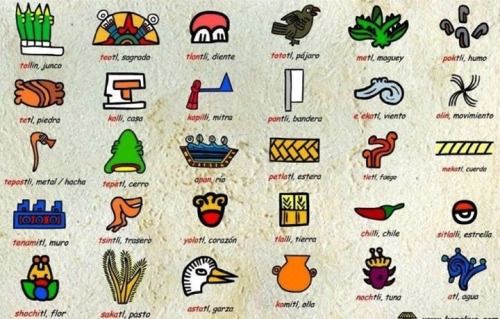

The pre-conquest Mexicans did not have writing in the same sense that Europeans at the time did; that is, there was no widely-used alphabet that represented specific sounds, and their written records often didn't look very much like those of the Spanish. Instead, they wrote pictographically, which means all of their words were in fact symbols and pictures that represented concepts instead of noises. There were symbols for specific noises, but they would never use them to write unless they were trying to describe something totally foreign to their language - why use three symbols to write B-OO-K when they could just use one symbol that meant "book", right? Why use a couple of different symbols that made up the sounds of "rabbit", when they could just draw a picture of a rabbit and be done with it?

The Spanish - and other European nations, when they eventually paid attention to what was going on in the southern New World - looked at these weird symbols and drawings and believed that the Aztecs must not be capable of reading or writing, and were instead relying on crude artwork to communicate because of this deficiency. In fact, the idea that they were a sub-literate people was one of the chief arguments in claiming that the giant urban civilization was in fact composed of savages, and that the influence of the Europeans was a benevolent thing that helped drag them up to the level of civilized culture. The fact that those self-same Europeans also burned the vast majority of Aztec codices they found, in order to prevent the natives from clinging to any pesky culture or religion they hadn't approved, resulted in very few of them surviving, which only fueled the idea back in Europe that the Aztecs couldn't write at all, poor dears.

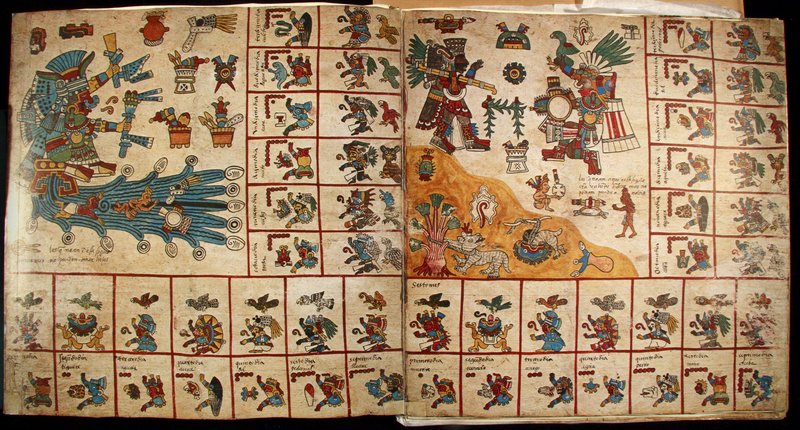

There's another layer of philological difficulty in play here as well, in that the surviving Aztec codices don't always have very much writing in them, either.

Well... shit. That looks bananas even to us, who are now used to different kinds of written communication, so imagine what it looked like to the conquistadors. There are clearly some symbols here, as well as some in medias res action scenes, but how the hell are you supposed to read that and come up with an actual story?

The answer is that you aren't, because the Aztecs didn't conceive of their codices the same way we do the printed word today. Books weren't something that you created and then anyone could just pick up and immediately get all the information out of (in fact, for most of the history of the written word across most of the world, books were considered something only the very wealthy or the priesthood was going to be able to read anyway); rather, many of them - especially those created for the clergy or religious rites - were actually intended to be performed instead of simply read. Instead of writing down as many words as possible to get the idea across to a reader, codices of this sort were filled with triggering symbols and relevant images, which were meant to be seen by a specially trained person (usually a priest) who had memorized the story that they were retelling. In essence, the codex was a compendium of mnemonic devices, designed to trigger a particular history, religious tale or edict in the mind of a person who had already memorized it, and then he would go ahead and verbally tell the story while referring to the codex for reminders and pictorial illustration.

This is one of my favorite incredibly neat things about the Aztec codices - that they're not just books, but actually performances, and that you need both the codex and the person who was trained to read it in order to get the full, beautiful impact of the story. It was both an artform and a complex way of storing important information - a synthesis of the more common methods in other cultures of either writing things down or passing them down orally with no written component.

Unfortunately, that system was almost totally destroyed with the coming of the Spanish. Not only did they have no interest in Aztec religious or historical book-performance (in fact, they severely discouraged it, since they wanted everyone to convert to European religion and law as quickly as possible), but they destroyed most of the codices, which in turn removed those all-important compendiums of story-triggers from play. Add in the fact that many Aztecs perished in the struggle over the empire, and you ended up with some ex-scribes or ex-priests who could have read the codices but never would again since they were now destroyed, trying to remember what they could without the compendiums they'd been taught to work with, or a few remaining codices that nobody could read, having lost whomever was trained to do so. Some histories written by Europeans who tried to ask Aztec people about reading them record that they actually refused to do so after a while - which was not surprising, considering that reciting forgotten lore about their native gods or sacred histories could get a native Mexican a one-way ticket to the Inquisition with blistering speed.

So the Spanish shrugged, said that the Aztecs obviously couldn't read or write, and sent a few of their pretty picture-books back to Europe as curiosities, and there the matter laid until a few centuries later, when scholars realized that there was actually a whole lot going on in the codices and that the idea that the Aztecs weren't literate because they used symbols instead of letters was about as ridiculous as saying that people from China couldn't read for the same reason.

Of course, just like we have in our society, the Aztecs had a lot of different forms of written communication, and the codices were only one of them. They also kept royal records and tax accounts, created elaborate maps and banners to mark places and people, and generally went about labeling things where useful about the way you'd expect. They just did so with colorful pictures instead of representative letters, leading to a sort of renaissance for modern archaeologists when they realized that they were actually looking at words and sentences, not just interesting artwork. Some codices do have phonetic writing in them, in both Spanish and Nahuatl, because they were written after the coming of the Europeans by Aztecs who had been partially assimilated into the new culture, while others are entirely composed of the combined-symbol glyphs of the pre-conquest artistic writing system.

By the way, the Mexica/Aztecs weren't the only ones to use codices this way; it was common in ancient Mesoamerica and the Mixtec and Zapotec also used the same style, which probably influenced the Aztecs into following suit. The Maya do have their own writing system, which is also glyph-based but a lot more elaborate and complicated (often compared to Mandarin Chinese), but it's an entirely different kettle of fish, one that has parts that are still being translated and puzzled out by scholars and archaeologists even today.

If you view writing as only words on a page, then it's possible you could say that the Aztecs didn't have it, but to do so would be to ignore their unique cultural advancements and methods of preserving their histories and beliefs, which were exciting and interactive in their own way. As a person who deals professionally in different ways of recording and sharing information, I never cease to be fascinated by the codices, or how much they can still tell us even centuries later and without their human half.

Is it bad that my brain instantly translated the title to "Tila Tequila"? I don't even like her. The brain does funny thing when it tries to quick-scan words.

ReplyDeleteHeh, with that many consonants in play, English-speaking brains are bound to be confused.

DeleteRecently watched some of her youtube channel....she has gone super crazy. Her channel is all conspiracy theory now. Aliens and magic powers she possesses.

DeleteMy brain immediately read tilapia. Im hungry....

ReplyDelete/pat

DeleteThis post is the best thing ever! The "performance" and needing the right person for it part is just full of awesome, and just begs to be put to use in a plot for a game!

ReplyDeleteIt's true - bring on the performing historian Scions!

DeleteThose Aztec Scions should jump on the Artistry train. Think of what they could do...damn, now I have to go and find a GM so I can do this.

DeleteWhat does the title mean?

ReplyDeleteLiterally, it means "The red, the black". Which is an idiom in Nahuatl that refers to written works, since those colors were those typically made via common inks.

DeleteNahuatl does a lot of this sort of thing. It's known as "disfrasismo", or disphrasis. It's a lot like Norse kennings. For example, young warriors would be referred to as "the eagles, the jaguars".

Nahuatl is so darn poetic when it wants to be.

DeleteThanks! :)

DeleteDarmok and Jalad, at Tanagra!

Delete(more fitting than you think)

I don't know who you are, but you can marry me. My current husband didn't love that episode enough.

DeleteIt was a good idea....handled clumsily!

DeleteSorry, you are past the 90 day return policy on used husbands. Also, we just don't want him back >=(

Delete