The main primary sources for Aztec mythology are the codices, which I'm sure you guys have heard me yell about until you're tired of me (did you know I have reproductions of some in my house, because I do!). Codices fall into two major groups: pre-Conquest, which were created by the Aztecs before any Europeans arrived to blow things up, and post-conquest, which were created by Aztec scribes who continued to write after the arrival of the Spanish and colonization of Mexico.

Pre-Conquest codices are, of course, the objectively "best" primary sources we have for Aztec mythology; because they were made before any European interference arrived, they give a clearer picture of the religion and history of the Aztec people. These include the Borbonicus, Borgia, Fejervary-Mayer and Vaticanus B codices, all of which are now preserved in museums and many of which are sadly fragmentary and incomplete. (That list is only Aztec/Mexica codices, by the way, but we also have a few pre-Conquest codices from other Mesoamerican peoples, including the Mixtec Nuttall and Selden codices, the Tlaxcallan Cospi codex, and the Mayan Dresden, Madrid and Paris codices. They're beautiful, but also difficult to read, since they're from the time period that priest-assisted codex performance would have been common and have little writing to go along with their symbolic and pictorial contents (although some Latinized writing in both Spanish and Nahuatl was added to a few of them after the conquest, especially the Borbonicus). They're lovely artifacts of history that some scholars have been studying their entire lives and still not fully explained every bit of iconography and myth, although many of them have certainly tried.

A page from the Codex Borbonicus, depicting Itzlacoliuhqui with the barb of Tonatiuh through his skull

A page from the Codex Vaticanus B, showing Mictlantecuhtli and Quetzalcoatl back to back

a page from the Codex Borgia, showing Tlaloc, Xochiquetzal and Chalchiuhtlicue

Unfortunately, we have way fewer pre-Conquest codices than we do post-Conquest ones. The vast majority of them were destroyed during the invasion by Europeans who either didn't see them as having any value or were trying to make sure the natives stopped practicing their religion so they could be converted to Christianity as quickly as possible. That brings us up to the time of the post-Conquest codices, which were made after the Aztec empire had been conquered. Unlike the earlier codices, which are mostly concerned with recording history and mythology, telling ceremonial stories and lauding the deeds of particularly awesome kings, the post-Conquest codices are much more a portrait of a people under duress. They tend more toward attempting to record what was happening in the here-and-now and tying it to what the Aztecs knew of their own history, and while some do have great mythological value, many of them intentionally leave out religious imagery or euhemerize it down to the deeds of men or demons to avoid the authors getting into trouble with the Catholic Church. Some, like the Duran Codex, were actually overseen personally by Spanish priests and officials who commissioned the works as gifts for royalty back home or had an interest in preserving native history, which naturally led to them being even more skewed toward the authors' attempts to avoid ending up on trial for heresy and the overseers' own commentary and interpretations. The most famous works of this time period are the Florentine, Magliabecchi, Mendoza, Telleriano-Ramensis and Xolotl codices.

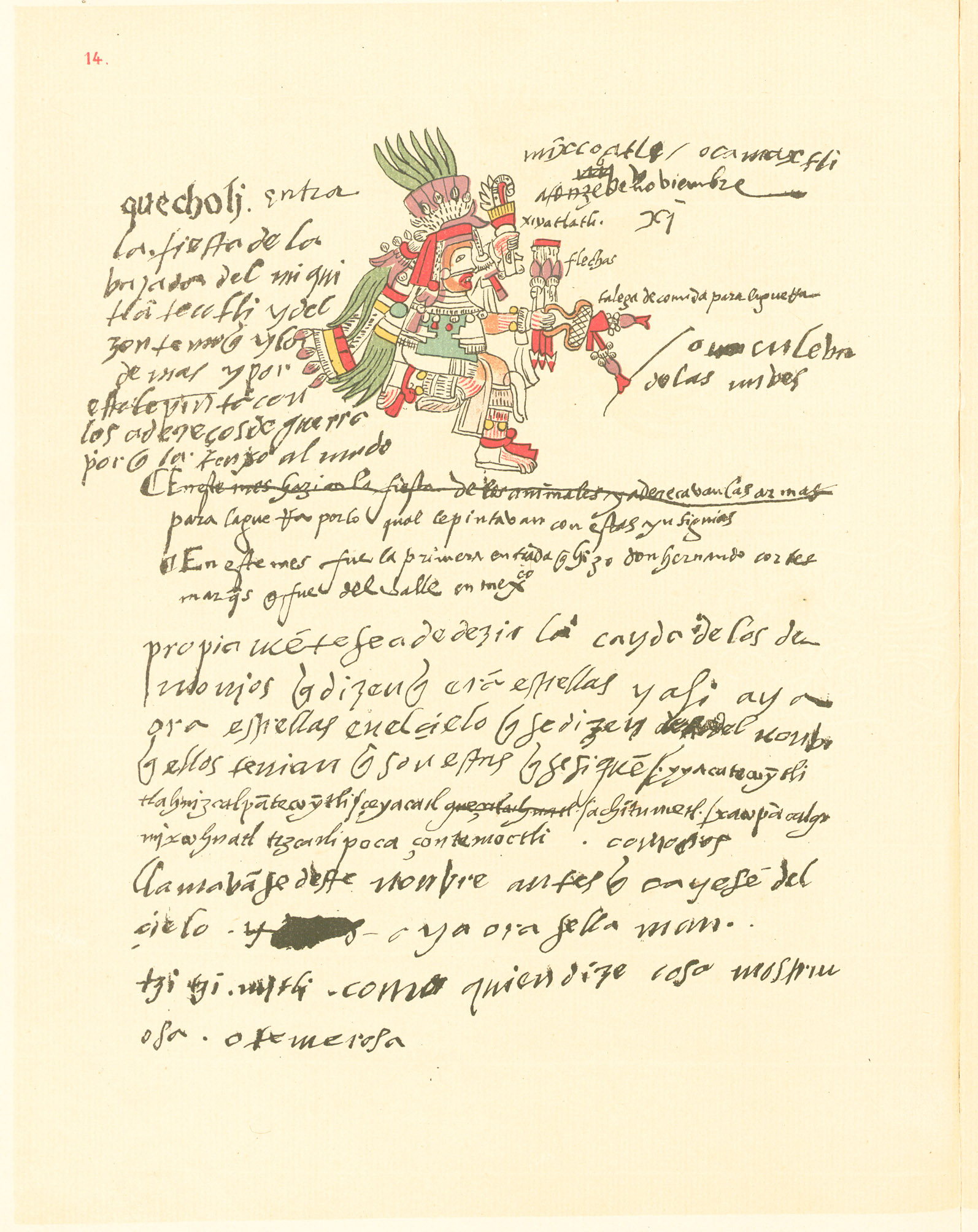

A page from the Codex Telleriano-Ramensis showing Mixcoatl with his hunting gear

A page from the Codex Mendoza showing Huitzilopochtli in eagle form leading the Mexica to found Tenochtitlan

A page from the Florentine Codex depicting Aztec human sacrificial rites

As you can see, these are much more Spanish- and writing-heavy - closer to the European idea of books than the older Mexican codices, because they were being written by people now living under European rule and for a mostly European audience. They are still major primary sources for the study of Aztec religion and myth (because frankly, they are what we have and beggars can't be choosers), but they also inspire a lot more doubt and raise numerous questions about how accurate their version of stories might really be and how much European interference might be coloring what they contain.

Like most conquered mythologies, we have to do a lot of our learning about them from secondary sources - outside chroniclers like Duran, reproduced historical sources like the Codex Chimalpopoca, or mentions of the culture's practices in preserved resources from nearby peoples who interacted with them.

By the way, since you mentioned it, the Popol Vuh is indeed the major primary source for Maya mythology and is awesome, but it has its problems, too. The version of the Popol Vuh we have today was recorded by a Spanish priest named Francisco Ximenez at the beginning of the eighteenth century, most likely after having the story orally told to him by a K'iche Maya person in what is now Guatemala, and it's been through many transformations and probable changes from that original storyteller to us. The K'iche version may have differed substantially from the Mexican myths of the classical Maya period, to start with - a few hundred years and a lot of geography separate the two, and while they are definitely the same culture and obviously telling the same basic story based on their artwork, we'll never know what details might be different unless we find some new buried source somewhere. Then, the story was recorded after being orally told, making it almost certain that the recorder probably colored it with his own interpretations or changed or omitted some of it; then, there are several theories about who wrote it down first and in what form before Ximenez recopied it to make the first manuscript that was widely passed around, which no doubt included his biases and interpretations; and then various scholars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries played academic hockey with the manuscript, recopying and even stealing it, until it finally came into the form we have today.

This is a pretty common story when it comes to preservation of myth. We'd love to always have an accessible, well-preserved priamry source by unbiased natives to take a look at, but in reality that almost never happens. Mexico and its mythologies are prime examples of the infernal mess left behind by invading cultures with little interest in preservation of the peoples who came before them.

In the Codex Borgia extract, I get that the dude on top is Tlaloc, but is the woman at the bottom Xochi or Chacha? And in either case, where's the other?

ReplyDeleteThe standing figure on the bottom right is Chalchiuhtlicue - you can usually recognize her by the water pot with the snake coming out of it. :) Xochiquetzal is the nude large-breasted woman sitting on the lower left.

DeleteThanks :)

DeleteHmm...I was expecting all three players to be of the same size. I was wondering, I know that in Egyptian Art, the height of a figure corresponds to his importance, which is why Pharaohs are always drawn as bigger than peasants and the Gods are giants; is there something similar going on in Aztec Art?

That's a general artistic principle called hieratic scale, you'll also see it often in Mesopotamian art

Delete